Un articol interesant despre A Dog of Flanders. Preluat de pe Crossroadsmag.

If you ask Japanese people what they know about Belgium, they will probably reply: “Oh yes, beers and chocolates”. But you would notice their somewhat quizzical look, indicating they do not really have a clear image of the country.

Then try this: “Do you know about Flanders?”

This time their reaction would be different. Their eyes would light up, and nodding strongly, they may start talking about Antwerp, not realising that the city is actually located in Belgium. They may start praising the beauty of its cathedral and to your astonishment, even embark on a precise description of the famous paintings by Peter Paul Rubens which can be admired inside.

Some of them might even begin to cry. By now you would feel totally confused, having no idea what caused them to become so emotional.

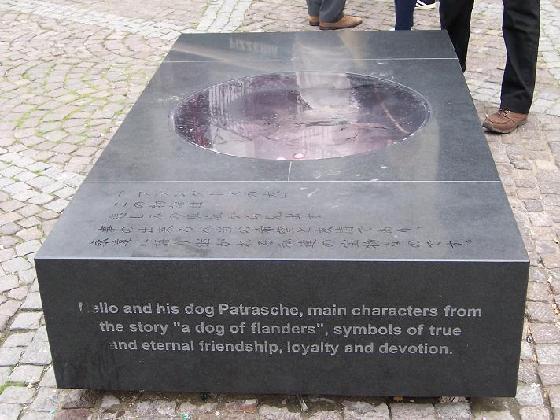

The name “Flanders” (Vlaanderen in Dutch, Flandre in French) refers to a region in northern Belgium and a constituent part of the federal Belgian state. But the word instantly reminds Japanese people of a particular story called “A Dog of Flanders”. In Japan, everyone, both young and old, knows exactly what happened to Nello and Patrasche in the cathedral of Antwerp on a cold winter night.

A beautiful and sad story

The original story “A Dog of Flanders” was written by a British-French author named Ouida, also known as Marie-Louise de la Ramée (1839-1908).

The book tells the story of Nello, an orphan boy who lived in a hut in the suburbs of Antwerp with his ailing grandfather and a dog named Patrasche. Nello earned money by selling milk in Antwerp, and Patrasche pulled the milk cart everyday. Despite poverty, they were the best of friends and very happy.

Nello was a naturally talented artist. He could not buy any painting tools but wanted to become a famous painter like Rubens, whom he admired very much. His dream was to see Rubens’ paintings in the cathedral one day. But these paintings were covered by heavy curtains, and he could not afford to pay a silver coin to see them.

Happiness did not last long. After his grandfather died a week before Christmas, Nello was falsely accused of causing a fire. Driven out of the small hut with no money, he went to the cathedral on Christmas Eve. Patrasche ran after him. The door was open by chance, and Nello saw Rubens’ paintings at last. On the following morning the young boy and his faithful dog were found frozen to death, tightly hugging each other in front of the paintings.

A tremendous success in Japan

This beautiful story itself follows a strange destiny.

Ouida spent only a few days in Antwerp in 1871. Her book was published the following year in Great Britain, and later went across the Atlantic to be distributed in the United States.

When she died in 1908 in Italy, the New York Times ran a lengthy obituary about her life and work. Ouida was depicted as a lover of dogs who spent most of her earnings on her beloved pets.

A Japanese diplomat, Masujiro Honda, who was stationed in New York, was touched by the article. He was fond of dogs too.

So he sent the English-language book titled “A Dog of Flanders” to his friends back in Japan. In his letter, he wrote: “This story is a masterpiece and the Japanese will love it.”

And they surely did after Honda’s friends translated the book that same year. It became one of the most well-known children stories for many generations.

Nippon Animation made an animation series based on the story in 1975. It was broadcast on national television, and children watched it at home every Sunday evening. As the story was nearing its end, the television station started receiving thousands of telephone calls and letters from children viewers, pleading: “Please don’t let Nello die!”. An emergency meeting was held, but after a long debate, the producers finally decided to be truthful to the original plot.

The series was a tremendous success, and since then, it has been shown on Japanese television again and again.

Jan Corteel’s mission

In 1982, Jan Corteel was working in his second year as a tourist officer in Antwerp. He can clearly remember the day when a young, tall Japanese boy came into his office at the Central Station. The boy asked him a question which would eventually change the rest of his life.

>“A Dog of Flanders, do you know?” the boy inquired in odd English.

Jan was born and bred in Antwerp but had never heard of it. “You mean the Lion of Flanders?” he said, referring to the symbol used by the Flemish army on 11 July 1302 when they defeated the French army during the landmark Battle of the Golden Spurs.

>“No, no. Not lion. Dog!”, the boy insisted.

Jan had to admit that he could not help him.

Later, Jan asked his colleagues at the tourist office. “Oh yes, they are looking for the dog for some reason, the Japanese tourists,” replied one colleague with a certain nonchalance, adding: “I think there is a book about it in the library.”

So Jan rushed to the library and indeed found an old book written in English. There were no Dutch or French translations. On the record of borrowers on the side of the book cover, Jan noticed that he was the fifth reader in a century.

He read the book over and over again. It was a story of Antwerp, Rubens, and the cathedral. He felt ashamed of not knowing the story. >“It was about us. I felt like the world was collapsing on me,” he remembers.

Jan was so devoted to studying the book that everybody thought he was mad.

He wanted to gather all the information available. So, when he would see Japanese tourists in town, he would ask them: “Do you know “A Dog of Flanders”?”

>“Of course we know. Why don’t you know?”, they all replied. Jan asked them to send him books and magazines from Japan, and soon his office was filled with Patrasche books. It was natural for him to decide to learn Japanese.

Jan’s findings

Then Jan began to wonder where Nello and Patrasche had actually lived. Ouida did not mention the name of the village, but did write that their hut was “a league from Antwerp.” A league was an old unit of distance used in Europe and equalled about five kilometres. “…on the edge of the great canal”: well, there is only one canal in Antwerp, the Scheldt (or Schelde in Dutch). And from the hut, the spire of the cathedral should rise “in the northeast.” It took him a year and a half of research to reach a conclusion.

It was Hoboken.

Hoboken used to be a village but is now part of an industrial area. Jan discovered that there used to be a large windmill in Hoboken. In the book, it was the place where Nello’s girlfriend Aloise lived with her family. According to local records, the miller who leased the mill had a daughter. She was the same age as Aloise, 12, when Ouida visited the village back in 19th century.

Thanks to Jan’s efforts, a small statue of Nello and Patrasche now stands in front of the information centre in Hoboken. Visitors can enjoy a walk to a rebuilt model of a six metre-high windmill and to a church where according to the book the boy and his dog were buried together. Many Japanese tourists take the 20 minute tram ride from Antwerp to see where their favourite story took place.

In the cathedral of Antwerp, tourists can now see the famous paintings by Rubens, “The Elevation of the Cross,” and “The Descent from the Cross”, without paying any additional coins (but they still need to pay an entrance fee).

Recent statistics prove Japan’s enthusiasm for the city. A total of 22,000 Japanese nationals visited Antwerp in 2003, ranking only second after Americans among non-EU tourists.

After 24 years of devotion to the story, Jan is now widely respected as an expert on Nello and Patrasche. Nobody thinks Jan is crazy anymore. Jan now has a Japanese wife, Yoshimi, whom he married five years ago. Having visited Japan 15 times, he can even explain the story to Japanese tourists in their own language.

When the Dutch translation of the book was published in 1985, Jan wrote in its foreword: “This story has been a ’secret ambassador’ for more than 100 years.”

“The story has come back to Antwerp at last. It travelled all around the world for 100 years. The Japanese people brought it back to us,” Jan says, smiling.

A true Belgian story?

However, the introduction of the story into Belgium proved no easy task.

In the tale, Nello was born in the Ardennes, and Patrasche was a Flemish dog. Wallonia and Flanders become friends, live in harmony. >“It’s a perfect Belgian story,” Jan thought.

So he brought the Japanese animation series to local television stations for broadcasting, but they all rejected it, pointing out that the clothing and buildings looked too Dutch and that they did not really depict “Flanders”. These differences might seem only small details to Japanese animators, but they were too big for the people in Antwerp.

In 1997, Nippon Animation and Japanese film producer Shochiku created an animated movie which was a remake of the successful television series. But this time, the staff first came to Jan for advice because they wanted to be accurate in every detail, so that the new production would also be accepted in Belgium.

After long talks, Jan finally succeeded to convince Belgian national television to broadcast the film. Since 2000, it has often been shown on Christmas Eve.

So may we conclude that Belgian people know the story now and that they too are deeply touched by its sad but heart-warming ending?

No. It is not that simple.

Culture: “A Dog of Flanders” revisited

I had a strange sense of déjà vu as I entered the cathedral of Antwerp. Although it was my first visit, the subtle gothic decorations on the walls and high ceilings seemed quite familiar. Standing speechless in front of Rubens’ paintings, I felt solemn and yet comfortable. Nello must have felt just the same, I imagined.

The climactic scene of the animation series “A Dog of Flanders” is almost like a common memory to all Japanese. No wonder many Japanese tourists weep for Nello as they think how he must have felt on that fateful Christmas Eve.

But I was surprised to learn that the Japanese are almost the only ones who get so emotional. Why do Belgians or Americans or British tourists not cry in the cathedral of Antwerp?

Some might say the Japanese are just too sentimental compared to all the realists in the world. But is that all?

“Well, we have learned there are more reasons to it,” say Didier Volckaert and An van Dienderen, a couple in Ghent who makes critical documentary films on current social issues. Their sixth and latest collaborative film, “Tu ne verras pas Verapaz” (2002) revealed the hidden historical facts of Belgian colonisation in Guatemala.

The subject of their next documentary is the story of Nello and his faithful dog Patrasche, the main characters of “A Dog of Flanders”. An and Didier were curious to know how their homeland was pictured abroad, and the story just seemed to fit perfectly in their project.

They have already travelled to Japan and gathered material for their film. An kindly shares some of their findings:

“As Belgians, this story reminds us of the poverty our forefathers suffered back in the 19th century. We simply cannot enjoy reading it,” she says.

“But a more important factor is the cultural difference in the acceptance of sad endings,” adds Didier. “Unlike the Japanese, we do not have the tradition of telling sad tales to our children.”

One may see an extreme but interesting example in how Americans have adapted the story. According to Didier and An’s research, there have been six different film versions of “A Dog of Flanders” in the U.S. since 1914, but none of them has a sad ending. American filmmakers always revise the tale into a “Happily-ever-after” story. Nello and Patrasche survive the cold winter night, Nello becomes a famous painter, marries his girlfriend Aloise…

It is a completely opposite approach from the Japanese animators who believed that the ending of the story was its most essential part and left it untouched.

“Americans think the original Patrasche story is just too harsh to confront children with,” Didier speculates.

Jan Corteel, a tourist officer in Antwerp and an expert on the story, also admits that there is a big perception gap.

“In our Western countries, one loses when he or she dies. But Asian people don’t see death as a failure. Devoting all your life with a true heart to the pursuit of a goal makes you an everlasting hero. And that is exactly what Nello did.”

As Jan puts it, “nobility of failure” may be another key factor. In Japan, there are traditional stories in which “the loser” receives more sympathy from the public than “the winner.” The Japanese even have a word for this: “hangan-biiki” which means feeling sympathy for a tragic hero.

Why do Japanese tell sad stories to their children?

“It has to do with how you raise your children in your culture,” discloses Akira Takahashi, a professor of developmental psychology at Musashino University in Tokyo.

In Japan, a basic principle of moral education and parenting is the idea of empathy. Children are taught to first consider what other people think and then decide how to behave. Parents and teachers will say: “If you act like this, think about what your friends will feel” or “It might make your mom feel sad.”

“But in the United States and maybe most other countries, parents and teachers act as the ‘authority’ figures and simply tell children what is right or wrong. Moral principles are social rules which exist outside of human relations. In Japan, morality is considered as something that you nurture by yourself as you grow up. This is just the way it is, and we can’t say which way is right or better.”

Takahashi suggests that children tend to empathise more deeply with sad feelings. Therefore Japanese people appreciate sad endings because they can use them as a kind of tool to teach children how to care for others.

He researched child-raising manuals for American parents and could not find any sad stories in their lists of recommended books. >“Children tales are supposed to give them dreams. Efforts should pay off at the end. Just like violent movies, sad stories are avoided in the U.S.”

Takahashi also found that the famous sad endings of Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” and “The Little Match Girl” have similarly been changed into happy ones in American versions.

What is Flanders?

Just as my quest is inseparable from the question: “Who is Japanese?”, the Patrasche story is also a way for Didier and An to explore the question “Who is Flemish?”

“The author of the book, Ouida, was British, and the book became popular in the U.S. and Japan. Everything comes from outside Flanders. We can see the Japanese animation series and exclaim: ‘This is not Flanders.’ But, then what is Flanders? We really don’t have the answer because we never asked ourselves this question,” An says.

The historical background of Flanders has made Flemish identity ambiguous. Since the 12th century the region fell under the rule of various neighbouring countries. Nowadays, an influx of foreign immigrants brings continuous social tension.

We will find out Didier and An’s answer when their film is released next year…

But do you like the story?

“So, did you like the story?” I asked Didier and An, who are both very fond of Japanese culture.\\ Didier, a fanatic of “manga” (Japanese comics), grinned:

“I really like the way the Japanese animators arranged the original book, but I had to laugh when it snows in the film. It’s like Siberia!”

OK. Forget about the little details for now.

But, I insisted, after all their research and interviews, I suppose they now see the story’s universal message, the celebration of friendship and devotion? They are surely moved by the sad ending?

“Not really,” An honestly admitted. “It is just too sentimental for me and I cannot concentrate on reading it through.”

“I liked the ending,” said Didier, “I now see the point in the death of Nello and Patrasche. But, did I cry? No.”

So maybe Japanese people are a bit sentimental after all.